JMJT! Praise be Jesus Christ! Now and Forever!

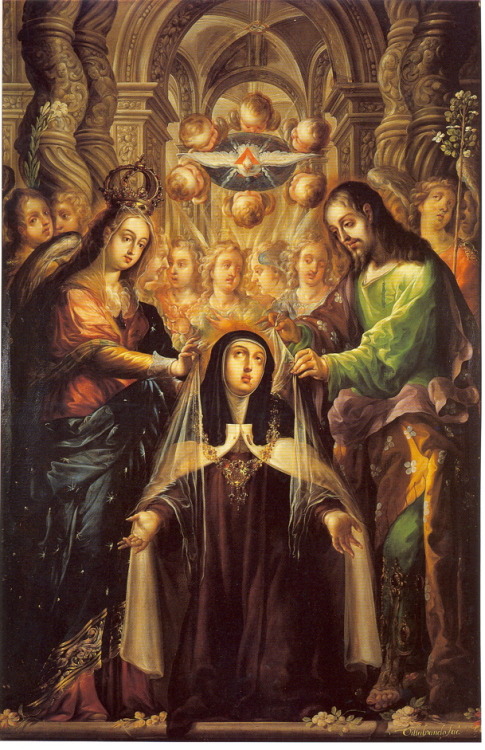

I just returned from a trip to New Mexico, where my husband and I spent time in both Albuquerque and in Santa Fe. I was struck by the rich heritage of Native American, Spanish, and Mexican cultures when one visits there. In particular, Santa Fe boasts the oldest mission in the United States at St. Miguel, and a vibrant art community that thrives on creating art in the style of Spanish Colonial style. The altar piece shown above is found in this mission, and depicts St. Teresa of Avila in the upper left-hand corner. This art celebrates the Catholic Church, Our Lord, Our Lady and Her saints. It recognizes that everyday human life is intrinsically interwoven with God's Will, love, and plans for each of us. It abounds with images of Our Lady and beloved saints which were painted on tables, mirrors, other various furniture, altar pieces, tabernacles, as well as found in framed pictures.

I was struck by several pieces which featured our Foundress, St. Teresa of Avila. According to Paul Rhetts, the co-publisher of Tradición Revista and an expert in Spanish Colonial Art, "Santa Teresa de Jesús (or de Ávila) is not a frequent image in the historic santos of New Mexico (from 1700-1900). According to ongoing research on the frequency and iconography of images by the author and funded by the Kriete Family Foundation, although Teresa appeared infrequently in the santos of New Mexico, she had a rather high degree of importance, evidenced by the fact that she may appear on five different altarscreens in New Mexico; only two other females appear more often on altarscreens — Santa Bárbara (12 times) and Santa Gertrudis (6 times). Santa Rosalía also appears five times on altarscreens in New Mexico. Teresa is the sixth most frequently found female saint (not including the Virgin Mary) in New Mexico. She makes up almost 5% of all the female images (not including the Virgin Mary) in New Mexico.

Some of the most important images of Teresa in the New World are:

Cristóbal de Villalpando, 17th century, Iglesia de San Felipe Neri, La Profesa, Mexico City, Mexico

Baltasar de Echave y Rioja, attributed, 17th century, Metropolitan Cathedral, Mexico City, Mexico

Juan Correa, late-17th/early-18th century, Churubusco, Museo Naciónal de las Intervenciones, Mexico City, Mexico (thought to have been displayed in the high altar of the first convent of Discalced Carmelite nuns founded in Mexico City, called Santa Teresa la Antigua, now defunct)

Juan Correa, 17th century, parish house at San Miguel Nonoalco in Mexico

José Nava, 18th century, Puebla, Mexico

Anonymous, 18th century, Monastery de Carmen Alto, Quito, Eucador

Anonymous, 18th century, Monastery de Santa Teresa, Cuzco, Peru

Anonymous, 18th century, Monastery de San Bernardo, Salta, Argentina

There are fourteen (14) known images of Teresa in New Mexico prior to 1900 by the following santeros: José Rafael Aragon (4), Arroyo Hondo Painter (2), José Aragon (2), Provincial Academic (1), Pedro Antonio Fresquis (1), Laguna Santero (1), and 3 by unknown artists. Five of the images are on altarscreens (Santa Cruz de la Cañada, San Miguel, el Santuario de Chimayó, Córdova, and the Upper Morada at Arroyo Hondo). Of the remaining nine images of Teresa, one is a bulto (by José Rafael Aragon), and eight are retablos.Iconography

A Spanish Carmelite in the 16th century, she was the leader of the reform of the order and the Counter Reformation. Born in Ávila, she lived from 1515-1582. She was a mystic writer and a Doctor of the Church. She was canonized just 40 years after her death.

She is seen wearing a nun’s garb usually of white and black (originally chestnut or maroon in color as an indication of the discalced order), often with a cloak; holding a crucifix, a crozier with a banner reading “IHS” and having the same emblem on her breast, and sometimes holding a palm. The final stage of her life, between 1555 and 1582, included many mystical experiences including a vision of Christ in his passion from which she advocated a life of retreat and piety.

Occasionally depicted in Spain with a doctoral biretta or mortarboard (she was proclaimed a doctor at the University of Salamanca). In the New World frequently seen with a book and pen. Pilgrim’s staff which ends with a double transverse cross as the founder of the reformed order. A dove, symbol of the Holy Spirit, is often seen above her as an indication of the sublimity of her writings. Sometimes with an angel who wounds her heart with an arrow, sometimes flaming at the tip, a symbol of ecstasy. Enamored with the suffering of Christ, she is said to have proclaimed “either suffer or die” (Aut Pati, Aut Mori) and “I shall sing about the mercies of the Lord forever” (Misericordias Domini in Aeternum Cantabo). She is often associated in the beloved souls in Purgatory, another possible connection with the Penitential Brotherhood.

There are as many as forty-two different scenes used to depict Teresa in the art of the New World — from her conversion and entrance to the Monastery of the Incarnation, through her visit with San Francisco de Borgia and receiving the communion from San Pedro de Alcántara, and to visions of Christ at the Column, the Holy Trinity, San José, Mary, and the Holy Spirit. In New Mexico all the scenes are of Santa Teresa as the mystic writer." (See http://nmsantos.com/Resources/Santo-List/Teresa/Teresa.html)

Since art is a means of creating beauty and telling a story, I thought I would share some of the beautiful pieces that I saw there as well as pieces found in other parts of the world where Spanish colonial art is prized. I hope that you enjoy!

Cuzco School: The Second Conversion of Saint Teresa. ca. 1694. Convento del Carmen

San Jose. Santiago de Chile. Photo: Mebold (1987, 77).

Adriaen Collaert (c.1560-1618) and Cornelis I Galle (1576-1650) designed a series of twenty four engravings on the life of Saint Teresa de Avila (see Gallery 5). This series served as the basis for two series of paintings on the life of the Saint currently in the Convento del Carmen San José (Carmen Alto) in Santiago, Chile. They are known as the Large Series and the Short Series on the Life of Saint Teresa (see Mebold 1987, 54-108).

The series of Collaert and Galle served as the basis of a series of sixteen paintings executed by José Espinoza de los Monteros en 1682 (Mebold 1987, 55). These paintings hang now in the Church of the Carmelite Convent in Cuzco, Peru. They are displayed on the nave of the church, eight per side. The last painting of the series bears the signature shown below (Mesa and Gisbert 1982, 92f).

The Large Series on the Life of Saint Teresa consists of thirteen paintings, each measuring two meters in height by two and a half in width. The Small Series on the life of the Saint consists of twenty paintings, each measuring 1.22 meters of height by 1.63 meters of width. Both series were produced by an unknown member of the Cuzco School of painting. Apparently, he was a follower of José Espinoza de los Monteros, the author of the Cuzco series on the life of Saint Teresa featured in Gallery 5. The Large Series was produced around 1690 and the Small Series around 1694 (see Mebold 1987, loc. cit.). (See http://colonialart.org/galleries/gallery-5-the-life-of-saint-teresa-cuzco-series)

| Luis Juarez Mexico 1585-1636 Saint Teresa of Avila and Her Companions (Fragment) 25.0322 | |

The Spanish mystic, St. Teresa of Ávila (1515-1582), who founded a religious order and who was the first woman to be named Doctor of the Church, was a popular subject in seventeenth-century art. Against her father's wishes, Teresa secretly entered the Carmelite convent in Ávila, Spain as a young woman. In 1652, she succeeded in founding the Convent of St. Joseph in Ávila, the first community of reformed, or Discalced Carmelite nuns (referring to their practice of going barefoot or wearing sandals.) This painting is consistent with the Counter Reformation style in Mexico, in which ecstatic holy figures were portrayed in an intimate, direct way. Holding a bishop's staff in one hand and with her other hand raised as if witnessing a miracle, she gazes lovingly at the prominent flowering tree. The tilt of her head and her pleasant expression make her appear approachable. The meaning of the tree, although assumed to be an allegory for some aspect of her life, or a passage from her writings, has yet to be determined. St. Teresa was an influential author. Among her writings are a spiritual autobiography, The Way to Perfection, advice to nuns, The Interior Castle, a description of the contemplative life, and The Foundations, an account of the origins of the Discalced Carmelites. [At the Figge Museum in Davenport, IA) See http://www.figgeartmuseum.org/Collections/Mexican-Colonial.aspx?page=4 Antonio Bisquert Antonio Bisquert

Saint Ursula, Saint Teresa of Ávila, Saint Rosalia, and the Eleven Thousand Virgins (1628)

Teruel Cathedral, Capilla de la Virgen de los Desamparados, Spain

| |

St. Teresa of Avila Receives the Veil and Necklace from the Virgin and St. Joseph by Cristóbal de Villalpando - 17th c